In the pursuit of examining any significant era in filmmaking, and perhaps horror films in particular, one must first gain an understanding of the time in which it happened, as history provides context. Without context, films are merely images on a screen, events without meaning and while they may still evoke an emotional response, we don’t truly understand the depth, the scope, of the emotions.

When the First World War came to an end in 1918, the Treaty of Versailles, dated 28 June 1919, required Germany, which had been defeated by the Allied Forces, to “Accept the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage” incurred during the war. In addition, Germany was forced to disarm, make territorial concessions, and pay reparations for damages caused to the civilian populations of the Allied nations and their properties. As with any event in which countries seek to make demands of those they vanquish, it is often the general population that has the least involvement, yet pays the highest price.

In other words, Germany was defeated, humiliated, and broke, left in a state of social, economic, and political bedlam. The reparations demand placed a heavy burden on the economy, leading to a period of hyperinflation, during which the value of German Mark plummeted and came close to ruining the country’s economy. The average citizens had no choice in the matter, no options they could exercise; rather, they were forced to make difficult sacrifices, which led to unrest and suspicion of convenient scapegoats, which ultimately set in motion the events that would, in 1933, bring about the rise of the Third Reich.

The generation of artists who came of age during this turbulent time were quick to assign blame on the preceding generation’s values and ideals; gone were the traditional notions of beauty and art, replaced by darkness, violence, and the emotional chaos felt by many in the post-war years. On painters’ canvasses and on motion picture screens, cities were in ruins, with their denizens lost in inescapable states of fear, rage, and paranoia. By an odd turn of events, Germany’s embargo against imported films caused a boom for its own motion picture industry, as the populace clamored for entertainment and distractions. Rather than offering fantasy-laden escapist fare, filmmakers chose to express the inner angst and confusion of the times in a stark and surreal fashion, creating films in which the inner turmoil spreads radially, concocting a world of distorted angles, deep shadows, and altered perception where no one, despite their alleged social standing, was immune from corruption.

Against this dark and emotionally brutal background, director Robert Wiene unleashed The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), the story of a traveling carnival, and one of its attractions, a somnambulist named Cesare (Conrad Veidt) who can answer questions about the future while in his sleepwalking state. Cesare is controlled by the mysterious Dr Caligari (Werner Krauss), whose motives may be far more sinister than providing mere carnival tricks. Cesare ventures out into the world at the hypnotic behest of his master, performing whatever tasks are demanded of him. It is within these scenes that Caligari is at its most masterful; surely, the idea of being completely controlled by another person, while in a sleeping state when one is at their most vulnerable, has been the subject of countless nightmares for untold generations, and calls to question the very sanity of existence. Indeed, insanity is a significant component not just in Dr Caligari, but in many films of the German Expressionist era.

Against this dark and emotionally brutal background, director Robert Wiene unleashed The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), the story of a traveling carnival, and one of its attractions, a somnambulist named Cesare (Conrad Veidt) who can answer questions about the future while in his sleepwalking state. Cesare is controlled by the mysterious Dr Caligari (Werner Krauss), whose motives may be far more sinister than providing mere carnival tricks. Cesare ventures out into the world at the hypnotic behest of his master, performing whatever tasks are demanded of him. It is within these scenes that Caligari is at its most masterful; surely, the idea of being completely controlled by another person, while in a sleeping state when one is at their most vulnerable, has been the subject of countless nightmares for untold generations, and calls to question the very sanity of existence. Indeed, insanity is a significant component not just in Dr Caligari, but in many films of the German Expressionist era.

As the tale of Dr Caligari plays out, it sheds many layers. When one believes they have the story puzzled out, it changes; the rug is pulled out from under the viewer so many times that it becomes difficult to accept the reality of anything projected on the screen. This may have been the ultimate goal of expressionist cinema: the disorientation of the viewer and the total immersion into a world at once disturbingly alien and yet eerily familiar.

Dr Caligari is a landmark work in the field of motion pictures; the actors are grotesquely made up and move in unnatural ways, making them appear at times to be controlled by unseen puppeteers (as many of the time no doubt felt, completely out of control of their own lives and destinies), while the sets are abstract and exaggerated, reflecting the ravaged landscape and emotional turmoil of postwar Germany. Shell-shocked and reeling from the devastating effects of war, it is not unreasonable to believe that many moviegoers felt a warped kinship with the sleepwalker as Caligari directs his every step. The effect of these efforts is that the viewer cannot help but to be drawn in, to experience the nightmare on a personal level, for the simple reason that there is no semblance of normalcy to cling to. In the expressionist world of Dr Caligari, nothing is as it seems, and no one is innocent.

Wiene’s unprecedented use of light and shadow was revolutionary for its time, providing a virtual blueprint for the horror and film noir genres that would soon find their genesis in Hollywood, particularly as German filmmakers would flee the country in ensuing years, as right-wing fanaticism gained a foothold and horrors far worse than those in films arose to lead Germany into unfathomable darkness.

By most estimates, the Expressionist era lasted seven to ten years, but its trademarks of anti-heroes, moral ambiguity, and inescapable human darkness have endured and earned a much-deserved place in the canon of filmmaking and film history.

The films of the Expressionist period struck a discordant resonance with audiences, even if they weren’t quite able to explain what exactly moved them. The psychological currents of a nation in decline were writ large upon the movie screen, and people turned out to see the elements that came to define the movement: anti-heroes, an underworld populated by criminals, madness, paranoia, and extreme use of light and shadow, to name but a few. While films of this time generally relied upon exaggerated sets that mirrored the chaos of the story and its characters, one film stood out for its use of locations that conveyed the same themes, and while its story took place in the preceding century, it came to define not just a style of filmmaking, but also a primary mythos of horror films, the rules of which are still followed to this day.

Nosferatu (1922), FW Murnau’s film about a vampire was almost lost to history; the story was taken from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Stoker’s widow went to court to have the film destroyed. All prints were burned, save but one, which had been traveling abroad. Without that single print, the film would be a mysterious footnote in history, not unlike London After Midnight (1927), all prints of which are believed to be lost.

Nosferatu (1922), FW Murnau’s film about a vampire was almost lost to history; the story was taken from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Stoker’s widow went to court to have the film destroyed. All prints were burned, save but one, which had been traveling abroad. Without that single print, the film would be a mysterious footnote in history, not unlike London After Midnight (1927), all prints of which are believed to be lost.

Nosferatu illustrates the growing of sense national xenophobia in a clever fashion; its antagonist, the vampire Count Orlock (Max Schreck) is shown as a beady-eyed, hooked-nosed, leering monster that sleeps in a box filled with dirt, and seeks to relocate from his home in Transylvania. This portrayal reflects the fears of many Germans, who were seeing immigrants pouring into the country with strange customs and unfamiliar appearances, bringing with them their money and religions, and the threat of their blood mingling with that of the German people. With these factors in mind, there is little wonder why this film was a success. In this landmark work of horror, the vampire, like the rats it sleeps with, is vermin, a literal plague carrier. It is no coincidence that vampiric folklore appears to have found its roots in Europe during the Black Death, and were vampires were suspected of being the source of the plague that claimed an estimated seventy-five to two-hundred million people in the fourteenth century. In a genre filled with beautiful, sensual and, perhaps most horrifyingly, sparkling vampires, it is important to realize that the cinematic birth of the undead bloodsucker shows it as a parasitic rodent.

In 1924, Robert Wiene and Conrad Veidt (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari) re-teamed for The Hands of Orlac, which tells the story of a concert pianist who loses his hands in an accident, only to have them surgically replaced with the hands of an executed killer. Orlac (Veidt) cannot play the piano with his new hands, but soon learns that the hands still carry their previous owner’s urge to kill. The feeling that one no longer has control over one’s own body or mind, coupled with advances in medical science, fueled fears over the loss of self in the midst of a changing world over which the individual had no control, are archetypal of the era. Orlac, while an Austrian production, is nonetheless considered an important film of the Expressionist movement.

In 1924, Robert Wiene and Conrad Veidt (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari) re-teamed for The Hands of Orlac, which tells the story of a concert pianist who loses his hands in an accident, only to have them surgically replaced with the hands of an executed killer. Orlac (Veidt) cannot play the piano with his new hands, but soon learns that the hands still carry their previous owner’s urge to kill. The feeling that one no longer has control over one’s own body or mind, coupled with advances in medical science, fueled fears over the loss of self in the midst of a changing world over which the individual had no control, are archetypal of the era. Orlac, while an Austrian production, is nonetheless considered an important film of the Expressionist movement.

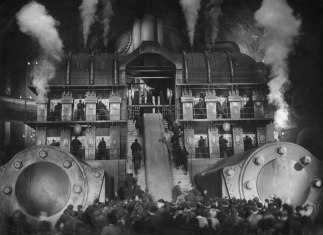

As the 1920s progressed, the themes expressed within the Expressionist era became more pronounced, as the gap between the privileged and the poor grew ever-wider, and the nation teetered closer to a breakdown, nowhere was this disparity been documented as spectacularly as in Fritz Lang’s masterpiece, Metropolis (1927).

While wealthy industrialists and their children live and play in aboveground luxury, the masses toil below, working at the machines that provide power for the city, in subhuman conditions. To die from exhaustion is a common occurrence, but a minor inconvenience, as there are always more ready and willing to enslave themselves to the machines. A chance occurrence leads a young man of privilege to see the world that exists just beneath his feet and it is from this revelation that the young man fights to bring the rich and poor together.

While wealthy industrialists and their children live and play in aboveground luxury, the masses toil below, working at the machines that provide power for the city, in subhuman conditions. To die from exhaustion is a common occurrence, but a minor inconvenience, as there are always more ready and willing to enslave themselves to the machines. A chance occurrence leads a young man of privilege to see the world that exists just beneath his feet and it is from this revelation that the young man fights to bring the rich and poor together.

The story of Metropolis echoes the desire of the industrialists who sought to overthrow the postwar Weimar Republic, and the working and unemployed classes who were left with no choice but to float along in their wake, assured of nothing but a future filled with uncertainty. Unfortunately, the collapse of the Republic led to the ascendency of failed artist and former prisoner (sentenced for treason) Adolf Hitler, whose rise to power would effectively bring an end to the already fading Expressionist movement, and ushering in an new era of unimaginable horror, forcing scores artists and filmmakers to flee their homeland. Not coincidentally, many German filmmakers found a new home in Hollywood.

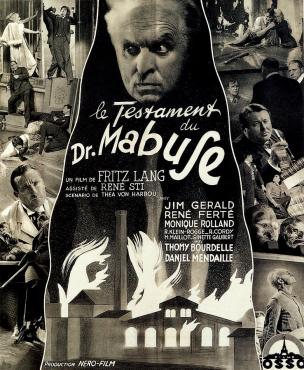

1933: Fritz Lang, acclaimed director of Metropolis (1927) and Dr Mabuse the Gambler (1922) finds that his latest film, The Testament of Dr Mabuse, has been banned by Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda under Adolph Hitler, stating that the film would be a menace to public health and safety, because it “showed that an extremely dedicated group of people are perfectly capable of overthrowing any state with violence.” Goebbels was, however, impressed enough by Metropolis that he extended to Lang the opportunity to make films for the Nazi party, which caused him to flee to Paris that night, according to Lang, although this accounting has been questioned.

1933: Fritz Lang, acclaimed director of Metropolis (1927) and Dr Mabuse the Gambler (1922) finds that his latest film, The Testament of Dr Mabuse, has been banned by Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda under Adolph Hitler, stating that the film would be a menace to public health and safety, because it “showed that an extremely dedicated group of people are perfectly capable of overthrowing any state with violence.” Goebbels was, however, impressed enough by Metropolis that he extended to Lang the opportunity to make films for the Nazi party, which caused him to flee to Paris that night, according to Lang, although this accounting has been questioned.

Whatever the case, the tide in Germany was turning, and it comes as no surprise that many of the first casualties of the rise of the Third Reich would be the artists, those who were able to communicate complex ideas to the masses; truly a terrifying ability in the eyes of those who sought to control those same masses. Starting around 1933, directors and actors Karl Freund, Billy Wilder, Max Ophuls, Curt Siodmak, Marlene Dietrich, Hedy Lamarr, Paul Henreid, Peter Lorre, Edgar Ulmer, and Douglas Sirk, to name but a few, emigrated to the United States due to a ban, by Goebbels, of all non-Aryan film professionals whose politics or lifestyles were considered unacceptable by the Nazi Party.

The flood of immigrants into Hollywood would have far-reaching effects on American filmmaking, particularly in the realm of horror films. Carl Laemmle, a German Jew who immigrated to the United States in 1884, founded Universal Studios in 1915. By the 1920s, Universal was making a name for itself in horror, with the legendary Lon Chaney proving to be a vital draw for the company with such films as The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). In 1928, Laemmle gave his son, Carl Jr, Universal Studios as a twenty-first birthday gift. Carl Jr went to work creating what is now known as the Universal Horror era, releasing Dracula and Frankenstein (both 1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), The Wolf Man (1941), and many others. Many of these now-classic films contain vital elements of the Expressionist style, such as heavy use of light and shadow, disfigurement, mental instability, mad science, loss of identity, and flawed antiheroes.

FW Murnau, director of Nosferatu, immigrated to the United States and was immediately put to work directing the silent masterpiece Sunrise, A Song of Two Humans (1927), which is widely considered to be one of the greatest films ever made, winning three Academy Awards in the Academy’s first ceremony. Sunrise makes use of the mise-en-scene, a common element of Expressionist cinema, to ‘bring’ the audience into the picture, utilizing all aspects of the shot, from sets, composition, costumes, music, and performances, all carefully composed to convey a specific message; in this case, the mise-en-scene takes the viewer into the heart and mind of a man and woman’s affair, which may lead to a devastating outcome.

FW Murnau, director of Nosferatu, immigrated to the United States and was immediately put to work directing the silent masterpiece Sunrise, A Song of Two Humans (1927), which is widely considered to be one of the greatest films ever made, winning three Academy Awards in the Academy’s first ceremony. Sunrise makes use of the mise-en-scene, a common element of Expressionist cinema, to ‘bring’ the audience into the picture, utilizing all aspects of the shot, from sets, composition, costumes, music, and performances, all carefully composed to convey a specific message; in this case, the mise-en-scene takes the viewer into the heart and mind of a man and woman’s affair, which may lead to a devastating outcome.

Of the homages to the German Expressionism movement, particular attention must be paid to Theodore Roszak’s 1991 novel Flicker, which takes the art of the era to a sinister level. Flicker is the story of Max Castle, a fictional German filmmaker who immigrated to the United States, making Poverty-Row movies, few prints of which still exist. Castle’s films utilize the darkness of shadows and the gap between frames (the ‘flicker’) of motion picture prints to install subliminal images that could, if the lost and missing films are seen, bring about tragedy of an apocalyptic scale, perhaps echoing the concerns of those who sought to ban such ‘subversive’ films in real life. Meticulous in detail and message, Flicker is a dense, disturbing, and fascinating look at the power of filmmaking, and an absolute must-read for any enthusiast of cinema.

Of the homages to the German Expressionism movement, particular attention must be paid to Theodore Roszak’s 1991 novel Flicker, which takes the art of the era to a sinister level. Flicker is the story of Max Castle, a fictional German filmmaker who immigrated to the United States, making Poverty-Row movies, few prints of which still exist. Castle’s films utilize the darkness of shadows and the gap between frames (the ‘flicker’) of motion picture prints to install subliminal images that could, if the lost and missing films are seen, bring about tragedy of an apocalyptic scale, perhaps echoing the concerns of those who sought to ban such ‘subversive’ films in real life. Meticulous in detail and message, Flicker is a dense, disturbing, and fascinating look at the power of filmmaking, and an absolute must-read for any enthusiast of cinema.

The impact of the Expressionist movement upon American and international cinema is immeasurable, with countless films, from The Third Man (1949) to Blade Runner (1982) to music videos (Rob Zombie’s Living Dead Girl is a loving tribute to The Cabinet of Dr Caligari,) owing much of their appeal, aesthetics, and emotional impact to a filmic movement created by a post-war desire for humiliation and blame-laying, and fueled by the rise of a nationalist fascist dictator.